[Makoto Shirakawa] Divergent routes to specialization: Guard cells, myrosin cells, and beyond

POST:

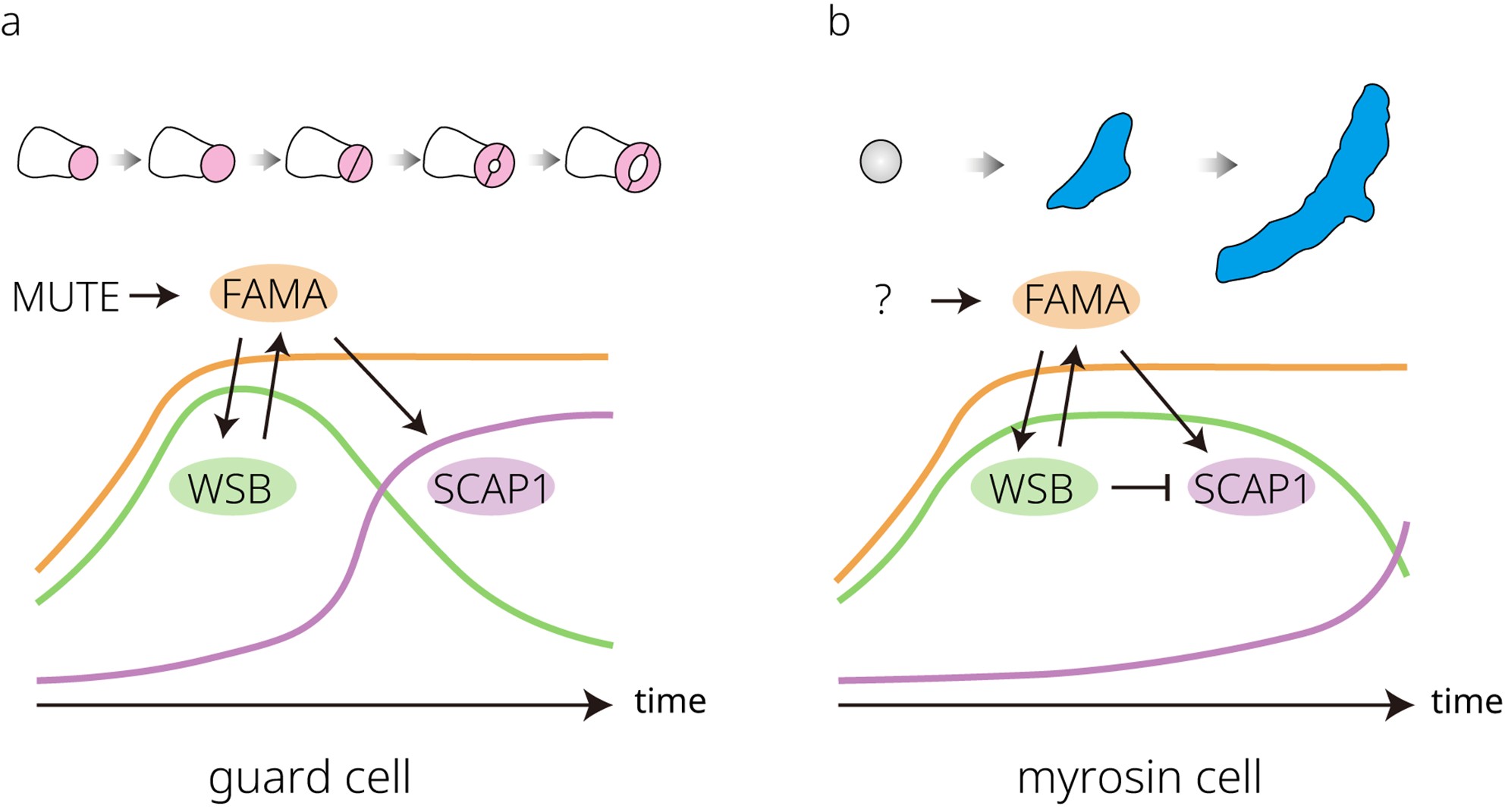

Developmental trajectories and regulatory dynamics of guard cells and myrosin cells. (a) In stomatal lineage cells, the bHLH transcription factor MUTE directly induces FAMA expression. Translated FAMA then regulates the expression of WASABI MAKER (WSB) and STOMATAL CARPENTER 1 (SCAP1). WSB is expressed earlier than SCAP1 in the stomatal lineage, showing a narrower expression window, although their expression windows partially overlap. SCAP1 expression increases later and persists in guard cells (GCs), where it is required for stomatal movement in mature GCs. Together with FAMA, these factors coordinate the final steps of GC differentiation. (b) Myrosin cells differentiate directly from ground meristem cells. FAMA expression is initiated in these cells and promotes WSB expression. WSB shows a broader expression window in myrosin cells than in GCs, in turn maintaining FAMA expression through a feedback loop. SCAP1 expression is repressed by WSB for most of the differentiation period but becomes detectable toward the end of maturation, perhaps contributing to the final steps of myrosin cell differentiation.

This review explores how plants generate new specialized cell types by reusing conserved transcription factors rather than inventing entirely new regulatory systems. We focus on the transcription factor FAMA, which controls guard cell differentiation and has been co-opted to generate myrosin cells, a Brassicales-specific defense cell type. Recent studies reveal that differences in the timing and persistence of downstream gene activation allow the same regulator to specify distinct cell fates. Single-cell transcriptomics further uncover unexpected myrosin cells in roots, highlighting developmental plasticity across tissues. Together, these findings illustrate how evolutionary rewiring of existing gene networks drives cellular specialization in plants.